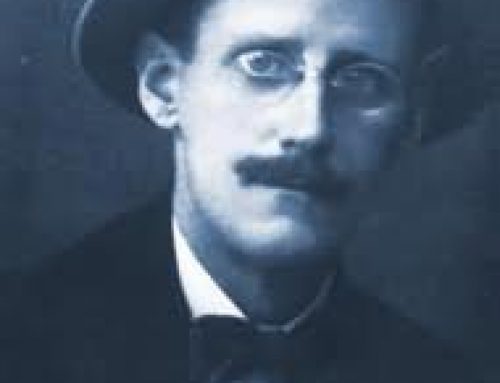

James Joyce’s « Ulysses, » first published in 1922, in a limited edition in Paris, is generally recognized as one of the 20th century’s greatest works of prose (if not the greatest) in the English language. It looms large as a work of art, a magnificent literary masterpiece, a modernist monument, and yet, as Stuart Gilbert wrote in 1930 in his landmark study of the book, “though ‘Ulysses’ is probably the most discussed book of our time, the book itself is hardly more than a name to many.’’ Decades later, in a new century and a vastly different, evermore materialist world immersed in the information age, Gilbert’s observation is still relevant, and perhaps even more pertinent today than ever.

« Ulysses » is the record of one ordinary day, June 16, 1904, in Dublin. The “hero” of this ordinary day is an ordinary man, Leopold Bloom, and the book is the « epic » of his ordinary day in all its minute and glorious banality. Bloom is everyman living everything. Everything indeed! Joyce’s method leaves nothing out; his is a spectacle of the whole of life. In this all-inclusive account of Bloom’s day, all is equal; one fact has no greater value than another for the artist. Bearing witness to whatever arises, Joyce practices a perfect equanimity in depicting his characters, just as they are. “Beautiful snowflakes!” an ancient Zen master exclaimed. “They don’t fall in another place.” Similarly, when asked by an interviewer why he had made Bloom’s father Hungarian, Joyce replied, “Because he was!” His is a portrait of life as an integrated, coherent whole, in which every detail is seen as it is, exactly in its place.

It can be said that the spiritual premise of the book is an all-encompassing acceptance of life, a fundamentally Buddhist notion. The author of « Ulysses, » a middle-aged Irishman exiled in an early 20th-century Europe torn by the savagery of war, was in accord with the Third Patriarch of Zen, who wrote, many centuries before in ancient China, “The perfect way is not difficult, it just dislikes picking and choosing.” He also echoes another traditional Zen saying: “The dharma is equal, no high, no low.”

Such is Joyce’s perfect way, and Bloom’s, and as such, Joyce’s work is eminently Eastern. The ordinariness of Bloom is that of Master Rinzai’s “true man of no rank.” Bloom, like Whitman, like each of us, contains multitudes. And he, like all beings and things, is without limits, in constant flux, endlessly flowing, like the River Liffey through Dublin to the sea.

Joyce also shatters our limited notions of time and space, depicting the present moment of each moment, on one specific day in one particular city. “Hold to the now, the here, through which all future plunges to the past,’’ says the other main male character, Stephen Dedalus. Indeed, we follow Bloom, Stephen and their fellow Dubliners throughout their city, throughout a Thursday at once unique and like any other. Joyce gives us unity of time and place, presenting only the here and now of each ever-changing here and now — hour to hour, morning to midday to night, bedroom to toilet to kitchen to office to cemetery to seaside to pub to brothel and back to bed again.

Like Homer before him, Joyce chose as his subject the odyssey of a voyaging hero. But Joyce’s “hero” is supremely human, exceptionally average, manifesting the unprepossessing greatness of basic goodness. Joyce gives us the quotidian heroics of one man in a single day. We are reminded of Bodhidharma, an ordinary man before the emperor, no merit, nothing holy. Joyce was fond of noting that the fabulously beautiful Helen, over whom the great armies of ancient Greece went to battle, would have been old and wrinkled by the time the Trojan War finally ended.

Like Shakespeare, Joyce takes the stuff of ordinary experience and, with his skillful means, weaves together the apparently disparate threads into an exquisite tapestry of life, just as it is. Every episode has a corresponding time, color, body part, and the 18 episodes are interconnected by common themes, events, thoughts, songs, bits of phrases, images, objects, places. As are the lives of the characters, in a thousand obvious and subtle ways. The book is alive, the One Body of the interdependent universe incarnate.

Joyce succeeds, too, in making style and subject one; the “shape” of his creation, and the myriad forms of language and style employed, manifest the endlessly open, ever-changing nature of all of life. Literary styles, like identities, it would seem, are not fixed. Joyce’s revolutionary use of what came to be known as the interior monologue brings the internal outside and the external inside, serving to make body and mind one. In structure and subject, « Ulysses » functions in triads, each group of three (episodes, characters, etc.) embodying two “opposites” and their unity. Likewise, through Joyce’s uncompromising depiction of diversity is revealed the underlying unity.

Innumerable themes wind through « Ulysses, » and different readers will seize upon different ones. Such is any reading of any of Joyce’s works, which are infinitely complex microcosms of the vast universe. Nonetheless, there is arguably a central theme in « Ulysses. » Stephen Dedalus asks himself early in the book, “What is that one word known to all men?” and then he proceeds to wander through the city all day and night seeking the answer, failing to see that it is always there before him. Deep in the night, Bloom, with an act of true compassion, will finally provide him the answer.

— Amy Hollowell Sensei

Leave A Comment